What is a git commit?

A git commit is the object that contains all the relevant information about your repository and files at the time of the commit. Commits are the git objects you’ll interact with most frequently, and everything in our series will build on this knowledge.

Commit ID

Git uses SHA-1 to calculate a hash of the commit object and the resulting hash becomes the commit ID. If any information about your commit changes, the SHA-1 hash will change (unless you’re intentionally running a collision attack, which is well outside the scope of this series, so we’ll ignore that possibility), thus resulting in a new commit object and a different commit ID.

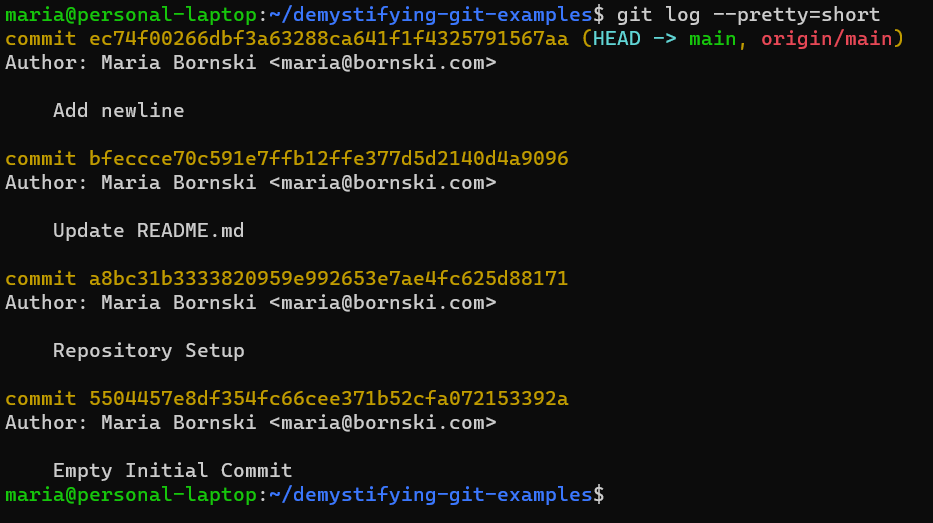

Command: “

git log --pretty=short“Snapshot of your files

For each commit, git stores a snapshot of all the files in your repository. This means that regardless of which files you changed in the commit, git can easily figure out the exact state of your repository at the time.

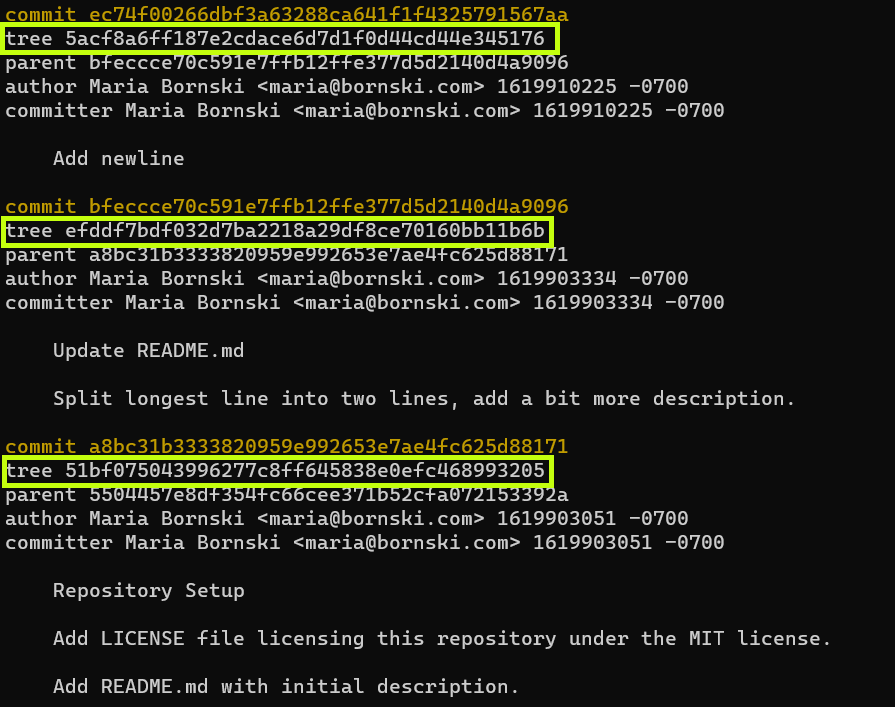

Git uses a “tree” object to contain information about other objects in your repository and uses SHA-1 to create a tree ID for each tree object. Any changes to the file contents, file names, or directory names in your repository will result in a different, thus resulting in a new tree ID for the new snapshot. The “Git Internals – Git Objects” chapter of the “Pro Git” book has a great deep dive if you want to learn more about git objects.

Command: “

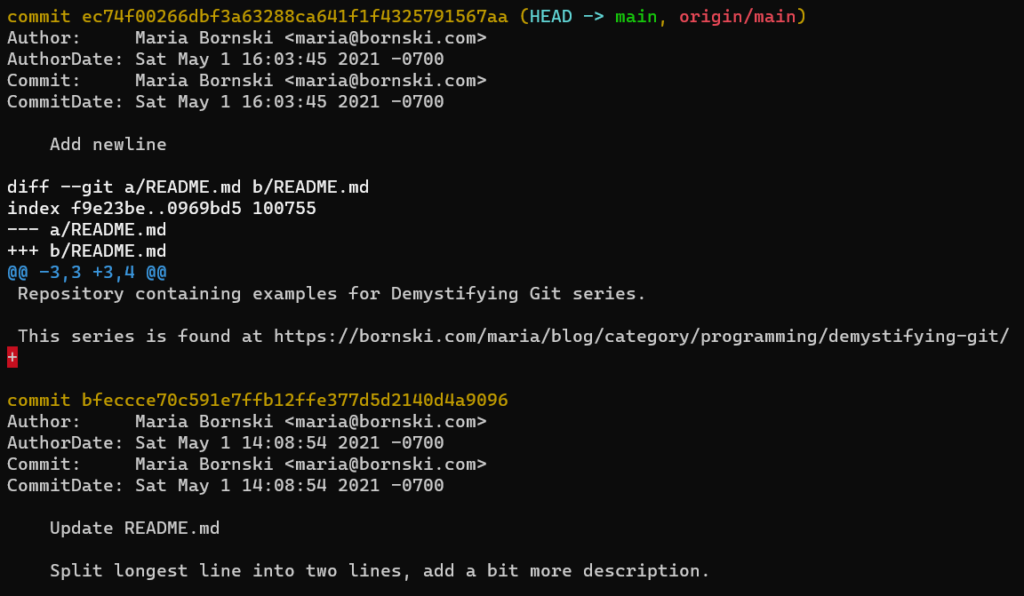

git log --pretty=raw ec74f0026“While git stores a snapshot of your entire tree, most commands to view git commits and git history display only the differences between commits. While this is often the information that someone wants to know, this method of display can mislead people into assuming git stores deltas or differences in the commit.

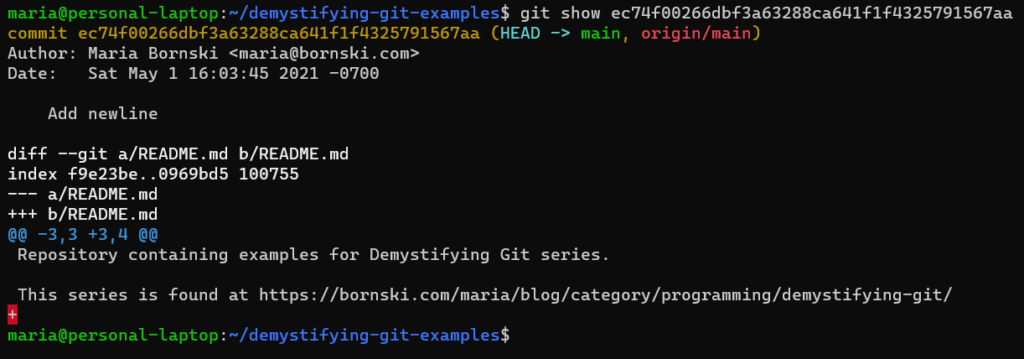

Command: “

git show ec74f00266dbf3a63288ca641f1f4325791567aa“Who and When

Git stores information about who worked on a commit and when the commit was created. Git was originally designed for Linux kernel development. In the Linux kernel community, developers who would like to make a change write their code and then send the change to the Linux kernel mailing list for discussion and code review. Once the relevant maintainer is satisfied, they incorporate the change into the kernel. This workflow means that more than one person is involved in every commit, so git keeps track of both Author and Committer information for each commit.

Author

The Author is the person who originally created the commit. The AuthorDate is the timestamp of when the commit was originally created.

Committer

The Committer is the person who created this exact commit. The CommitDate is the timestamp of when this exact commit was created.

Viewing and updating Author and Committer

You can view the Author and Committer information by adding --pretty=fuller to commands like git log and git show. When you first run git commit and create a commit object, the Author and Committer information will be the same.

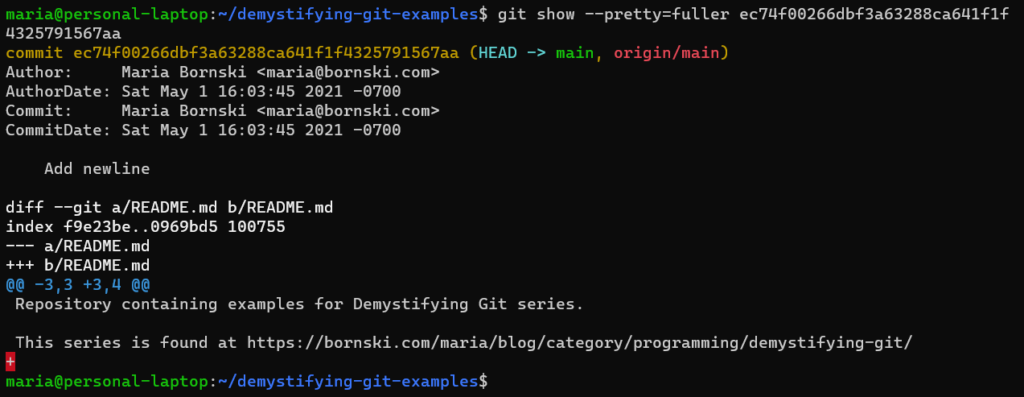

Command: “

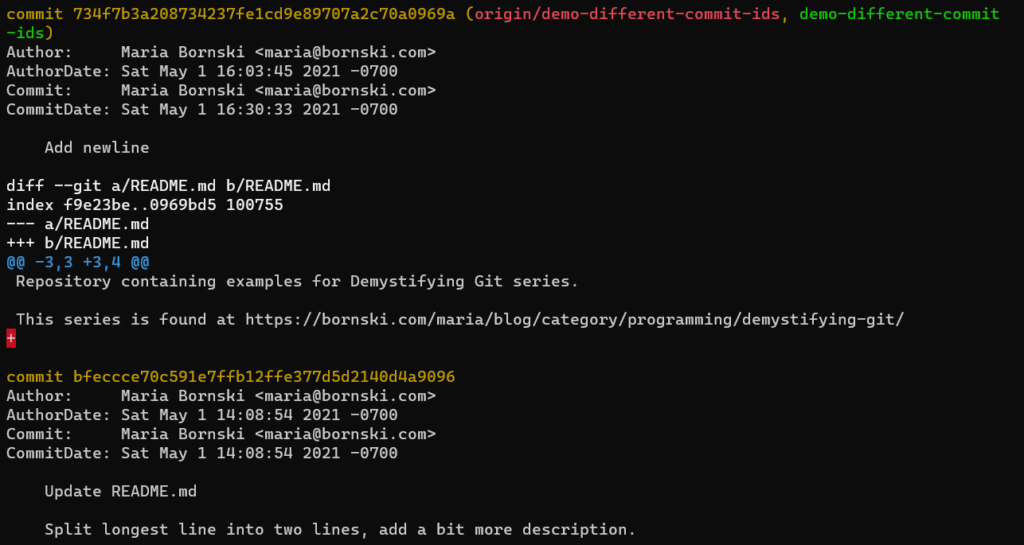

git show --pretty=fuller ec74f00266dbf3a63288ca641f1f4325791567aa“Any changes to the commit via commands like git cherry-pick, git rebase, or git commit --amend will update the Committer information but leave the Author information alone.

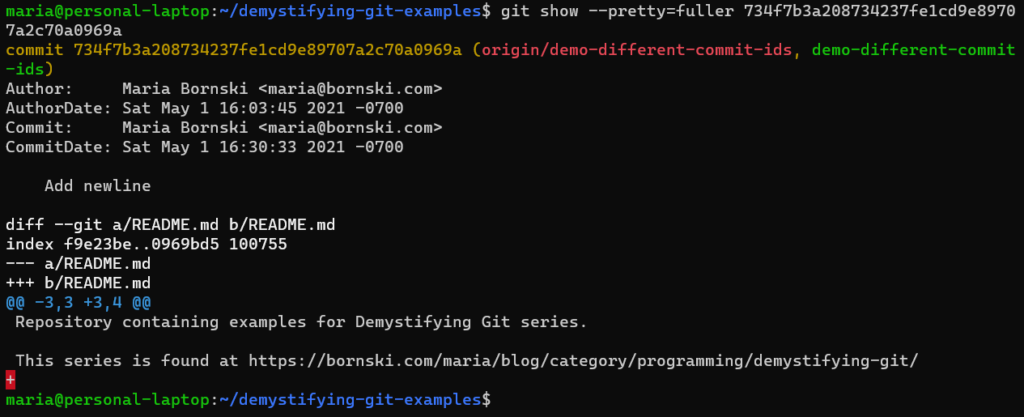

Command: “

git show --pretty=fuller 734f7b3a208734237fe1cd9e89707a2c70a0969a“By default, git log will display the Author and AuthorDate, which can make history look a bit surprising. If you see a commit that says it was made earlier than the prior commit, it probably actually has a later CommitDate!

Parent commits

Git stores the commit ID(s) of any parent commits in each commit object. The very first commit in a repository will not have a parent commit.

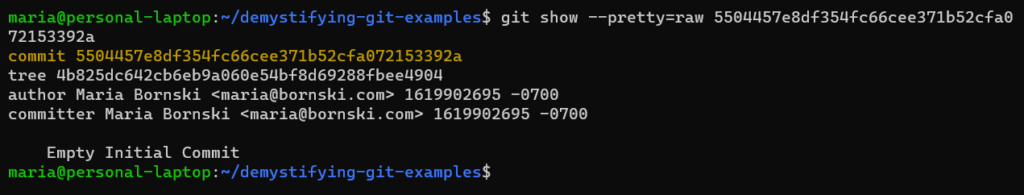

Command: “

git show --pretty=raw 5504457e8df354fc66cee371b52cfa072153392a“Merge commits will have multiple parent commits — One for each branched merged together. Most commits will have a single parent commit: the most recent commit on the current branch in your working directory at the time you created the commit.

Commit message

The git commit message lets you explain your commit to your future self and other people looking at the repository. As with all other aspects of the commit object, any changes to the commit message will result in a new commit ID.

How does this affect working with git?

Comparing Commits

In the strictest sense, git commits are only the same if they are the literal same object — eg, they have the same commit ID. Two commits may make exactly the same changes to your files but if they have different parent commits, commit messages, Author information, or Committer information, then they are not the same commit.

As a concrete example, these commits are identical except for CommitterDate. They therefore have different commit IDs, so they are different commits.

Other Impacts

We’ll talk more about how commit objects affect git workflows in future installments!

Try it for yourself!

All examples on this post were created using https://github.com/mariabornski/demystifying-git-examples and git version 2.25.1 on Ubuntu 20.04.1 LTS (GNU/Linux 4.19.128-microsoft-standard x86_64).

You’re welcome to go clone the repository yourself & try out the commands! Similar commands will work on any git repository, you’ll just need to substitute your own commit IDs.